Rehan Khan

On 8th November, the Supreme Court, by a 4:3 majority, held that the minority status of an educational institution does not end simply because it is regulated by a statute or administered by non-minority members. This ruling, in the case of Aligarh Muslim University Through its Registrar Faizan Mustafa v. Naresh Agarwal and ors, overruled the 1968 judgment in S Azeez Basha vs. Union of India, which had previously held that Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) lost its minority status due to its establishment under a parliamentary statute.

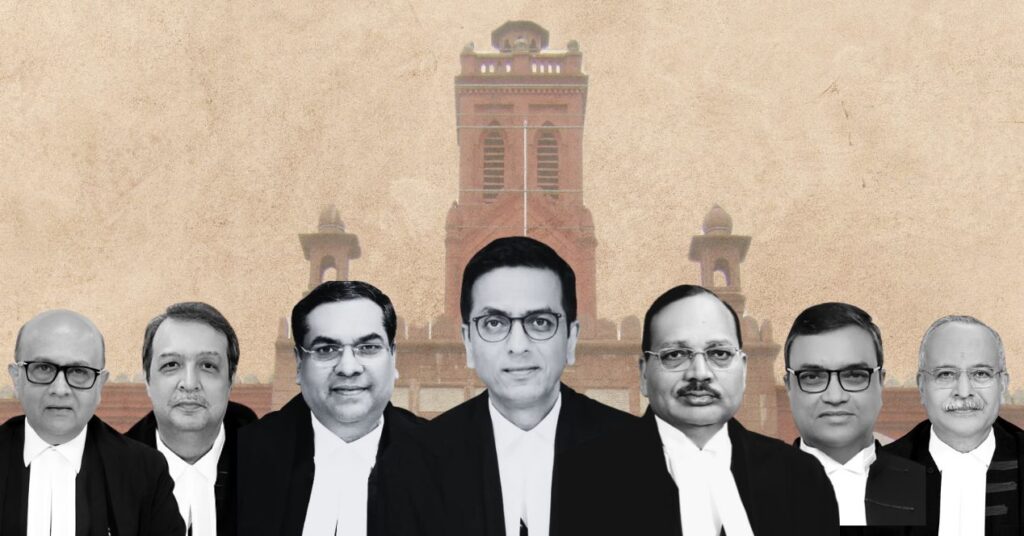

A Seven-Judge Constitutional Bench led by Chief Justice of India (CJI) DY Chandrachud, along with Justices Sanjiv Khanna, Surya Kant, JB Pardiwala, Dipankar Datta, Manoj Misra and SC Sharma, clarified that an institution’s minority status is fundamentally tied to its establishment by a minority community, rather than its administration by minority members or the passage of regulatory statutes. The majority emphasized that “the view in Azeez Basha that minority character stops when statute comes into force is overruled” and noted that AMU’s minority status would be determined by applying this interpretation in a regular bench’s factual examination. CJI Chandrachud emphasized that the Court must assess “the genesis of the institution and who was the ‘brain’ behind its establishment.” Thus, determining minority status would depend on the institution’s original founders and the community primarily responsible for its creation.

The Bench further underscored that regulation by the government, including statutes enacted under Article 19(6), does not inherently infringe on an institution’s minority character, provided such regulation does not interfere with its core identity as a minority institution. CJI Chandrachud stated, “An educational institution established by any citizen can be regulated under Article 19(6) provided it does not infringe the minority character of the institute.” Addressing the interpretation of Article 30, the majority held that this provision, which guarantees minorities the right to establish and administer educational institutions, applies to institutions created before as well as after the Constitution’s enactment. The ruling specified that Article 30 would be “diluted if it only applies to institutes established post-Constitution.”

However, the decision was not unanimous, as Justices Surya Kant, Dipankar Datta, and Satish Chandra Sharma dissented on several critical points. Justice Surya Kant raised objections regarding the propriety of referring the case to a seven-judge Bench, originally done by a two-judge Bench in 1981, questioning whether such a small Bench could effectively “dictate” the composition of a larger one. Justice Kant argued, “In my opinion, the reference was not in accordance with judicial propriety…a two-judge Bench should not dictate how a larger Bench is constituted.” On the merits, he maintained that for an institution to claim minority status, it must satisfy both establishment and administration requirements under Article 30, implying that AMU would need minority oversight in administration to retain such a designation. Justice Kant suggested that a regular bench, rather than a seven-judge Bench, should ultimately resolve AMU’s status.

Justice Dipankar Datta shared Kant’s procedural concerns and rejected the premise that AMU qualifies as a minority institution. He asserted that AMU could not be protected under Article 30 because it was not exclusively administered by minorities, arguing that adherence to both establishment and administration by minorities is essential for Article 30’s protections. Justice Datta elaborated, “If we allow minority status without full minority administration, we risk diluting the intent behind Article 30.” He further noted that the earlier references in 1981 and 2019 were unwarranted and should not set precedent.

Justice Satish Chandra Sharma took a slightly broader stance, arguing that Article 30’s crux is to prevent preferential treatment for the majority and ensure equality. In his view, minority institutions that claim Article 30 rights must be both established and fully administered by the minority group, thereby excluding outside administrative influences. Justice Sharma opined that both the “establishment” and “administration” criteria must be applied conjunctively, with administrative authority over aspects like hiring and day-to-day operations resting solely with minority members. According to Justice Sharma, “Established and administered must go hand-in-hand; one cannot be compromised for the other.” He also criticized the notion that minorities still need safe havens within education, arguing that they are fully integrated into mainstream society, participating equally across various sectors.

Click here to access the judgement.

Case Title: Aligarh Muslim University Through Its Registrar Faizan Mustafa Vs. Naresh Agarwal

Case Number: C.A. No. 002286 / 2006 and connected matters

Bench: Chief Justice of India (CJI) DY Chandrachud, Justices Sanjiv Khanna, Surya Kant, JB Pardiwala, Dipankar Datta, Manoj Misra and SC Sharma