Nithyakalyani Narayanan. V

In a case involving the minority status of Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), the Supreme Court noted that an educational institution is not prohibited from enjoying minority status merely due to the fact it is governed by a statute.

A Constitution Bench of Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud, Justice Sanjiv Khanna, Justice Surya Kant, Justice J B Pardiwala, Justice Dipankar Datta, Justice Manoj Misra, and Justice Satish Chandra Sharma held that a minority group does not need to have absolute administration in order to claim such status under Article 30 of the Constitution, which guarantees minorities the right to establish and manage educational institutions.

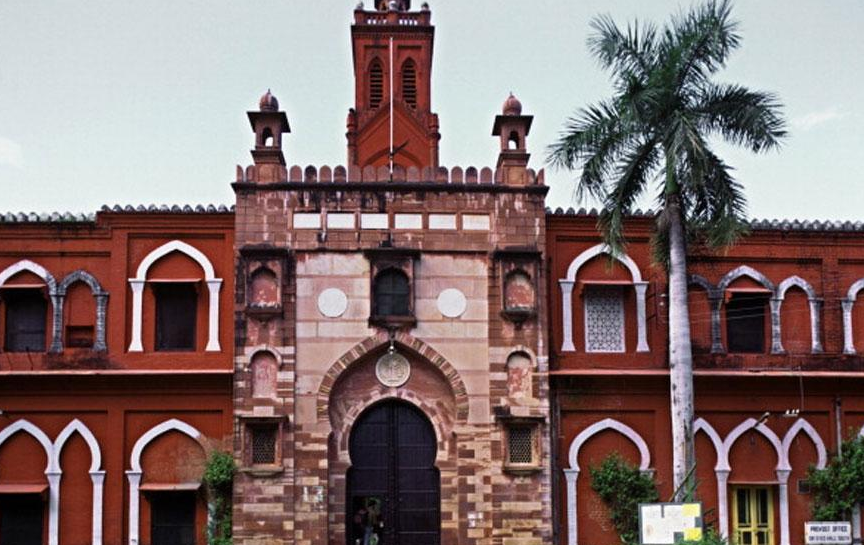

The Aligarh Muslim University’s minority status was the issue in the case the court was hearing. The questions of law include whether a university founded by parliamentary statute that receives central funding can be classified as a minority institution and what conditions must be completed for an educational institution to have minority status under Article 30.

In February 2019, the case was assigned to a seven-judge bench presided over by the then Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi. In the 1968 case of S Azeez Basha v. Union of India, the Supreme Court declared the University to be a Central University. In the aforementioned case, the Court further declared that a Central University could not be granted minority status in accordance with Articles 29 and 30 of the Indian Constitution. The University’s minority status was later restored when the AMU Act was amended. This was contested before the Allahabad High Court, which overturned the action on the grounds that it was unconstitutional. As a result, AMU immediately filed appeals with the Supreme Court. Notably, the Central government retracted their appeal in the case in 2016.

Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, appearing for the Central government, first objected to AMU portraying the issue as a re-examination of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Azeez Basha’s case when the case was brought before the court. AMU was represented by Senior Advocate Rajeev Dhavan, who contended that the Azeez Basha ruling’s legality needed to be considered in light of potentially conflicting later rulings.

The bench questioned one of the petitioners supporting the university’s minority status to explain why the designation was significant given the institution had performed well in other ways over the previous 100 years.

Farasat, representing petitioner Hazi Muqeet Ali Qureshi, highlighted that AMU’s status as a minority university would negatively impact Muslim women’s access to higher education in India – “It’s a fact in the community that it sends their children, especially women, to AMU because of its minority status. The court has to take into account some social realities. Minority status of AMU and education for Muslim women have gone hand in hand”.

In response, the court questioned Farasat about the implications for AMU’s standing of the seven-judge bench’s decision to eventually overrule Basha or designate the university as a minority school.

Farasat retorted that AMU’s status has always been suspended, with the exception of the reservation issue, because the case has been pending before the Supreme Court since 1967 at various points, adding that if the seven-judge court were to uphold the 1967 Basha ruling, AMU would lose its minority status for the first time.

The judges stated at one point that the “core issue” to be decided would be whether the 1967 ruling by the Supreme Court rejecting AMU’s application for minority status was correct – “If Basha was wrongly decided, it will mean denial of minority status was wrong. So, if we conclude Basha was wrongly decided, the very basis of the high court judgment (in 2006) goes because the high court said Parliament could not have overruled Basha through the 1981 amendments. So, that’s the core issue”.

The bench held that it might not strictly abide by the current case’s facts in order to establish general guidelines for when an institution might be classified as a “minority institution” for the purposes of the Indian Constitution.

The court additionally stated at one point in the hearing that the Constitutional clause does not require that administration be done by the minority itself. The court was called upon to interpret the terms “establish and administer” under Article 30, which defines a minority institution.

On January 23, the court will take up the subject for further hearings.

By way of Solicitor General (SG) Tushar Mehta’s written submissions, the Centre informed the court on Tuesday that it had decided in 2016 to withdraw its support for AMU’s minority status based only on “constitutional considerations,” as the former UPA government’s position to pursue it legally was “against public interest” and went against the public policy of reservation for marginalised sections.

Name of the case: Aligarh Muslim University Through its Registrar Faizan Mustafa v Naresh Agarwal and ors.

Bench: CJI DY Chandrachud, Justice Sanjiv Khanna, Justice Surya Kant, Justice J B Pardiwala, Justice Dipankar Datta, Justice Manoj Misra, and Justice Satish Chandra Sharma.