Rehan Khan

Introduction

Reservations in educational institutions and public services for marginalized sections continue in India, though they were not originally mandated by the Constitution. Initially, these measures were left to the government’s discretion for ten years, often used for political purposes. The Constituent Assembly aimed to address historical exploitation; a goal supported by the judiciary to ensure representation.

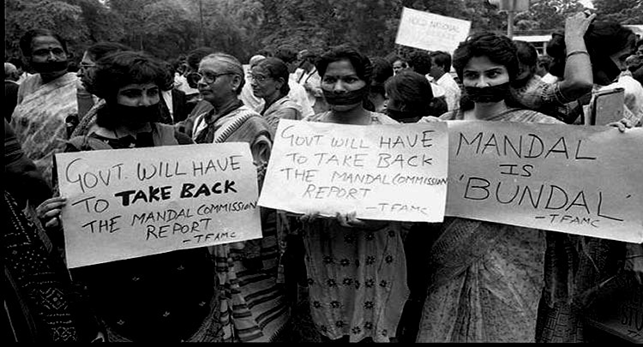

The landmark case of Indra Sawhney & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors. (1992) is a pivotal example. Amid protests against the Mandal Commission’s 27% quota for socially and educationally backward classes (SEBCs) in central jobs and institutions, this nine-judge bench decision reflects ongoing debates on reservations. This article simplifies and analyzes the case, examining its impact through transformative constitutionalism, subsequent rulings, and the current socio-political context.

Facts and Brief History

In 1953, the Government of India set up the first Backward Classes Commission under the chairmanship of Kaka Kalelkar. The Commission’s mandate was to determine the criteria for identifying socially and educationally backward classes and recommend measures for their advancement. The Commission was established in response to the provisions of Article 340 of the Indian Constitution, which emphasize the need to investigate the conditions of backward classes and suggest ameliorative actions.

The Kelkar Committee submitted its report in 1955, highlighting several key findings:

- Identification of Backward Classes: Criteria included social, economic, and educational indicators such as traditional occupation, educational attainment, and social status.

- Caste as a Criterion: Caste could be one criterion for identifying backwardness but should not be the sole factor. A combination of social, economic, and educational factors was recommended.

- Reservation Recommendations: Measures included reservations in educational institutions and government jobs, but no specific percentage was provided.

- Emphasis on Education and Economic Development: Recommended improving educational facilities and economic opportunities through scholarships, special coaching, and vocational training programs.Top of FormBottom of Form

The Government of India did not fully implement the recommendations of the Kelkar Committee, which relied heavily on caste as a criterion for identifying backward classes. This controversial reliance and the subsequent governmental inaction led to demands for a more robust approach to uplift backward classes.

In 1979, under Prime Minister Morarji Desai, the government established the Mandal Commission, chaired by B.P. Mandal, to identify socially and educationally backward classes (SEBCs) and recommend measures for their socio-economic improvement. The Mandal Commission, formed under Article 340 of the Indian Constitution, submitted its report in 1980, identifying 3,743 castes as SEBCs and estimating they constituted about 52% of India’s population. The Commission recommended a 27% reservation for OBCs in central government jobs and public sector undertakings, in addition to the existing 22.5% reservations for SCs and STs, totalling 49.5%.

For nearly a decade, these recommendations were not implemented. In 1990, Prime Minister V.P. Singh announced the implementation of the Mandal Commission’s recommendations, leading to a 27% reservation for OBCs in central government jobs. This sparked widespread protests and agitations, with opponents arguing the policy was politically motivated and would undermine meritocracy.

The announcement led to a series of legal challenges. Indra Sawhney, a former civil servant, filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court challenging the constitutionality of the decision, contending that the reservation policy violated the principle of equality under Article 14 of the Constitution and would lead to inefficiency in public administration.

Issues Raised

- Constitutional Validity of Reservations for OBCs: Whether the 27% reservation for OBCs in government jobs and educational institutions violated the principles of equality enshrined in the Constitution of India.

- 50% Cap on Reservations: Whether the total reservations, including those for SCs and STs, exceeding 50% were constitutionally permissible.

- Exclusion of the Creamy Layer: Whether economically advanced individuals within the OBCs should be excluded from the benefits of reservations.

- Reservations in Promotions: Whether reservations should be extended to promotions in government services in addition to initial appointments.

Petitioner’s Arguments

- Violation of Equality: The petitioners argued that the implementation of the Mandal Commission’s recommendations violated Article 14 of the Constitution, which guarantees equality before the law. They contended that reservations based on caste alone would perpetuate caste divisions and inequality.

- Meritocracy: They argued that exceeding the 50% limit for reservations would undermine meritocracy and lead to inefficiency in public administration. The petitioners asserted that reservations should be limited to ensure that merit remains a key criterion in government employment and education.

- Creamy Layer Concept: The petitioners contended that economically advanced individuals within OBCs, often referred to as the “creamy layer,” should be excluded from reservations to ensure that the benefits reach the genuinely disadvantaged sections.

Respondent’s Arguments

- Historical Injustices: The respondents argued that reservations were necessary to address historical injustices and social discrimination faced by the backward classes. They contended that affirmative action was essential for achieving social equality and providing equal opportunities.

- Social Representation: They emphasized that the 27% reservation for OBCs, in addition to the existing reservations for SCs and STs, was crucial for ensuring adequate representation of all sections of society in public employment and education.

- Application of Creamy Layer: The respondents acknowledged the need to consider the “creamy layer” concept to prevent economically advanced individuals within OBCs from availing themselves of benefits of reservations. They argued that this would ensure that the benefits reach those who truly need them.

Judgment

In a historic judgment, the Supreme Court upheld the 27% reservation for OBCs, stating that it was constitutionally valid and necessary for social upliftment. However, the Court imposed a ceiling limit of 50% on the total reservations, including those for SCs and STs, except in extraordinary circumstances. This was to ensure that the principle of equality was not compromised.

The Court introduced the concept of the “creamy layer,” directing that economically advanced individuals within the OBCs should be excluded from availing themselves of benefits of reservations. This was to ensure that the truly disadvantaged sections within the OBCs benefitted from affirmative action.

Additionally, the Court ruled that reservations should not extend to promotions in government services, emphasizing that such a practice would undermine efficiency and merit.

Impact and Significance

The Indra Sawhney judgment has had a profound and lasting impact on India’s reservation policy. By upholding the 27% reservation for OBCs while imposing a 50% cap on total reservations, the Supreme Court sought to balance the need for affirmative action with the principles of equality and merit.

The introduction of the “creamy layer” concept was a significant step towards ensuring that reservations benefit the genuinely disadvantaged sections of society. This concept has been applied in subsequent policies and legal interpretations, shaping the framework for affirmative action in India.

The ruling also underscored the importance of periodic reviews of reservation policies to ensure their effectiveness and relevance. It reinforced the need for a balanced approach to social justice, one that addresses historical injustices while maintaining the integrity of constitutional principles.

The Indra Sawhney case continues to be a cornerstone in the discourse on social justice and affirmative action in India. It has influenced subsequent legal and policy decisions and remains a key reference point for debates on reservations and social equality.

Case title: Indra Sawhney & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors., AIR 1993 SC 477.

Case no.: Writ Petition (Civil) No. 930 of 1990.

Bench: Justice M.H. Kania, Justice M.N. Venkatachaliah, Justice S.R. Pandian, Justice T.K. Thommen, Justice A.M. Ahmadi, Justice Kuldip Singh, Justice P.B. Sawant, Justice R.M. Sahai and Justice B.P. Jeevan Reddy