Nancy Suryavanshi

Abstract

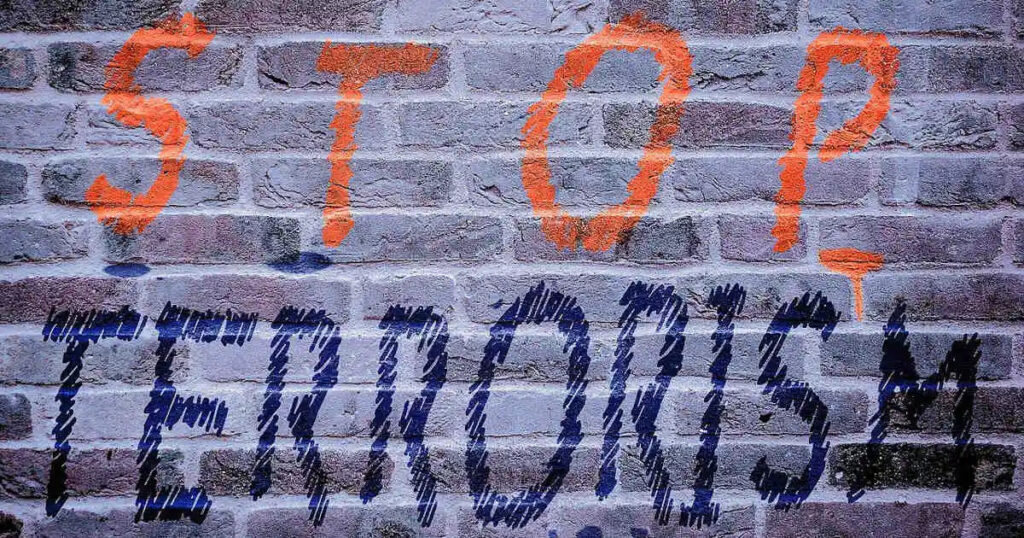

The Global Terrorism Index Report, 2022, ranked India 12th among the countries where citizens have died as a result of terrorism. Terrorism has emerged as the most recent threat to international peace and, in particular, to India’s national security. Terrorists are becoming more sophisticated and capable in every aspect of their operations and assistance. The terrorists are not only threatening the ideals of democracy and freedom but also causing a serious challenge to the existence, progress and development of mankind. For the prevention of terrorism, strict provisions are required. If legislation against terrorism is implemented in a country like India, it should be so strict that the perpetrator is brought to justice and does not get away with it because of loopholes or flaws. The importance of special laws to combat terrorism cannot be overstated; however, the difficulty lies in their implementation and the abuse of powers granted to authorities under the special laws.

Introduction

The term terrorism is derived from a Latin word that means “great fear.” Terrorism as a tool for achieving political goals is not a new phenomenon, but it has taken on a new severity in recent years. In terms of intent, it differs from all other crimes. The term “terrorism” was initially used during the French Revolution (1789-1799), when Jacobins, the revolutionary state’s rulers, used violence, including mass executions, to force compliance from his people. Although the concept of terror and terrorism has varied from person to person and place to place, the United States Code of Federal Regulations has provided a precise definition of terrorism.

Terrorism in India

India has been losing people due to terrorism in numerous forms, ranging from domestic to foreign to novel forms such as narco-terrorism and cyber-terrorism. Terrorism has been a common occurrence in our country. Despite the broader legal framework, this is taking place. The Indian Penal Code, the primary Indian Substantive Criminal Law, and the newly passed Information Technology Act, 2000 all attempt to address the country’s worries about terrorism. A terrorist to one person is a freedom fighter to another. India has seen some of the world’s worst terror acts in the name of ideological superiority. The Mumbai attack of 2008 is a heart-breaking example. Terrorism has long been regarded as a grave danger to the rule of law, peace, and order.

Laws Dealing with Terrorism in India

India is known to be a part of the strategic triangle- India, America, and Israel against terrorism and fundamentalism. India being a part of this triangle has tried to implement stringent laws in the form of ‘Special Enactment’ to deal with the menace caused by terrorism. Since the Independence of India, various laws in the form of special enactment, rules, regulations, ordinances, etc have been implemented. Some of them have been repealed and various new ones have been enacted. With nearly 748 terror occurrences recorded in 2018, India ranks third among the countries that have seen the most terrorist acts. According to reports, 350 Indians were killed and 540 were injured in these instances. [1]

India’s Terrorism Laws

Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002 (POTA): In wake of the 1999 IC-814 Hijack and 2001 Parliament attacks, there was a clamor for a more stringent anti-terror law, which came in the form of The Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA), 2002. A suspect could be detained for up to 180 days by a special court. The terrorist organisations were included. The Union government could add or remove any organisation from the schedule.

Finally, on September 17, 2004, the Union Cabinet approved ordinances repealing the controversial Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002 (POTA) and amending the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, in accordance with the UPA government’s Common Minimum Programme. The government would allow a one-year sunset period during which the Central POTA Assess Committee will review all POTA cases, according to Home Minister Shivraj Patil. He went on to say that after the ordinance is passed, no arrests will be made. To fill the gap left by the repeal of the Act, adequate amendments to the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 were made to define a terrorist act and provide for the banning of terrorist organisations and their support systems, including funding, attachment, and forfeiture of proceeds of terrorism, among other things. After POTA is repealed, all terrorist organisations that were previously prohibited will continue to be banned under the Unlawful Activities Act. The onus on the accused to prove his innocence, mandatory denial of bail to the accused, and admission as evidence in a court of law of the confession made by the accused before the police officer are some of the elements of POTA that would be fully removed in the new Unlawful Activities Act.

Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA): The Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987, was at one time the main law used in cases of terrorism and organised crime, but due to rampant misuse, it was allowed to lapse in 1995. The Act defined a “terrorist act” and “disruptive activities”, put restrictions on the grant of bail, and gave enhanced power to detain suspects and attach properties. The law made a confession before a police officer admissible as evidence. Separate courts were set up to hear cases filed under TADA. TADA was challenged in the country’s highest court as being unconstitutional when it was enacted. In the case of Kartar Singh vs. State of Punjab, the Supreme Court upheld its constitutional legitimacy on the presumption that individuals entrusted with such draconic statutory power would act in good faith and for the public benefit. However, there were numerous cases of power abuse for personal gain. TADA expired on May 24, 1995, however, the Maharashtra Control of Organized Crime Act of 1999, which went into effect on April 24, 1999, is another important anti-terrorism law in India. TADA was challenged in the country’s highest court as being unconstitutional when it was enacted. In the above case, the Supreme Court upheld TADA’s constitutional legitimacy on the presumption that individuals entrusted with such draconic statutory power would act in good faith and for the public benefit. However, there were numerous cases of power abuse for personal gain. TADA expired on May 24, 1995, however, the Maharashtra Control of Organized Crime Act of 1999, which went into effect on April 24, 1999, is another important anti-terrorism law in India.

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA): In 2004, the government chose to strengthen The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967. It was amended to overcome some of the difficulties in its enforcement and to update it in accordance with international commitments. By inserting specific chapters, the amendment criminalised the raising of funds for a terrorist act, holding of the proceeds of terrorism, membership of a terrorist organisation, support to a terrorist organisation, and the raising of funds for a terrorist organisation. It increased the time available to law-enforcement agencies to file a charge sheet to six months from three.

The law was amended in 2008 after the Mumbai attacks, and again in 2012. The definition of “terrorist act” was expanded to include offences that threaten economic security, counterfeiting Indian currency, and procurement of weapons, etc. Additional powers were granted to courts to provide for attachment or forfeiture of a property equivalent to the value of the counterfeit Indian currency, or the proceeds of terrorism involved in the offence. Under UAPA, unlawful acts are those that are believed to endanger India’s integrity and sovereignty, while terror activities are those that are intended to endanger India’s security or strike fear in its citizens. These definitions are broad and ambiguous. As in the Bhima Koregaon conspiracy case, this allows alleged Maoist ideas and ties to be prosecuted under UAPA. What is being treated as a terrorist act in the case alleging an insurrectionist conspiracy behind the Delhi 2020 riots is public resistance to the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019, which protestors have termed discriminatory to Indian Muslims and a violation of India’s secular constitution. In effect, this statute allows the state to equate opposition to government policies and laws with treason and insurgency, limiting acceptable citizen action to being “neither overtly hostile to the government nor loudly wishing for political change, as well as (having) at least, a working relationship with majoritarian sentiments,” according to law scholar Shahrukh Alam.

Conclusion

I think there is a need for stringent provisions for the prevention of terrorism. In a country like India if a law regarding terrorism is enacted it should be made so stringent that the culprit is brought to book and does not go scot-free just because of loopholes or lacunas in the ordinary law. Also, we need to consider that our neighbouring nation Pakistan which is the cause of perpetrating terrorism in India has also enacted stringent laws something which India also needs to follow diligently. The primary functions of criminal law are to identify a crime, categorize it fairly, and prescribe punishments based on appropriate punishment theories. Anti-terror laws in India have been shaped for obvious reasons. To prevent terror attacks, rigorous legislation is urgently required. In a country like India, it’s essential that when anti-terrorism laws are implemented, they’re made so strict that the offender is brought to justice and doesn’t get away with it because of loopholes. The establishment of the National Investigation Agency Act (NIA), 2008, as the first step toward effective handling of terrorism-related offences, is the most significant recent development. The Central, State, and municipal governments are all responsible for combating terrorism. This Act envisions a partnership between the federal government and the states in the investigation of terrorism cases. Furthermore, citing the threat of terrorism, India’s Home Minister has announced the formation of a National Counter Terrorism Centre (NCTC) modelled after the US NCTC for systemic reform in information collection and the functioning of several agencies. As a result, former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan correctly stated that respect for human rights, fundamental freedoms, and the rule of law are essential tools in the war against terror.

[1] https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-111shrg49484/html/CHRG-111shrg49484.htm

Views are personal.

The author is a law student at NMIMS School of Law, Bangalore and is currently interning at Desi Kaanoon as a Content Writer.