Rehan Khan

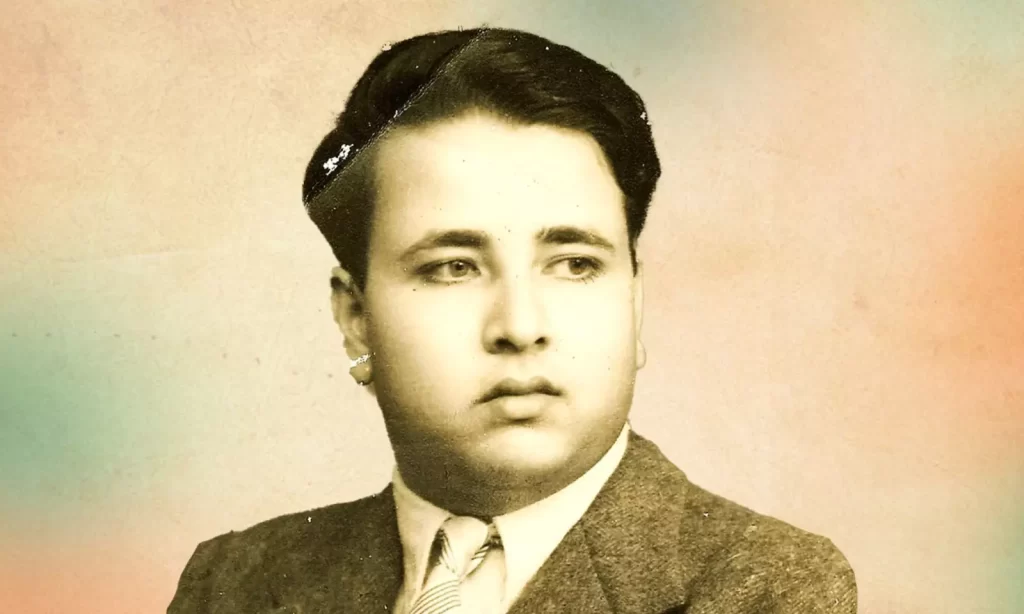

On August 11, we commemorate the birth centenary of Akbar Imam, a remarkable barrister whose life and career were as distinguished as they were unconventional. Born into the illustrious Imam family, Akbar’s journey in the legal profession was marked by brilliance, humility, and a unique blend of tradition and modernity.

Akbar Imam, born in Patna to Justice Syed Jafar Imam and Asma Imam, was part of a family that has been central to the legal history of India. Justice Jafar Imam, Akbar’s father, was the senior-most puisne judge of the Supreme Court and was expected to become the Chief Justice of India. However, due to health issues, Justice P.B. Gajendragadkar assumed the position earlier than anticipated. Justice Jafar himself was the son of Sir Ali Imam, a barrister who served in various prestigious positions, including a High Court judge, a member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council, and Prime Minister of Hyderabad State. The family’s legacy in law, as highlighted in Justice Sudhir Katriar’s book, The Patna High Court: A Century of Glory (2015), has left an indelible mark on the Indian legal landscape.

Akbar’s education was as impressive as his family background. He attended St. George’s School in Mussoorie before studying science at Trinity College, Cambridge. Later, he was called to the Bar from the Middle Temple in London. Returning to Patna, Akbar began his legal practice, specializing in criminal law. Despite his relatively young age, he quickly established himself among the few barristers in Patna, rubbing shoulders with formidable figures such as Dharamshila Lal, the first woman lawyer of the Patna High Court, and K.D. Chatterji, later the Advocate-General of Bihar.

Akbar’s practice in Patna brought him into contact with several notable colleagues, including Justice Leila Seth, who would go on to become the first woman judge of the Delhi High Court and later Chief Justice of the Himachal Pradesh High Court. Leila, in her autobiography On Balance (2003), fondly recalls her friendship with Akbar, describing him as having a lively and unrestrained personality. She shares anecdotes of how Akbar, despite his serious profession, would sit in his chambers reading poetry and eating chocolate, much to the dismay of his clerk, who was keen to project a more traditional image to potential clients.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Akbar’s career was his penchant for flying. In the late 1950s and 1960s, Akbar would pilot his two-seater L5 plane from Patna to Delhi, with a refueling stop at Lucknow. His companions were either his white-bearded senior munshi, Majid, or his junior munshi, Lakhan. Upon landing at Safdarjung airport, he would proceed to argue his cases in the Supreme Court. This mode of travel was not just for his Supreme Court appearances; Akbar also flew to district towns in Bihar and present-day Jharkhand for trials, provided there was a suitable landing spot. On occasions when his clients could not arrange a car, Akbar would ride pillion on their bicycles, displaying a humility that was as admirable as it was rare among lawyers of his stature.

Akbar’s versatility extended beyond the courtroom and the cockpit. He was an accomplished oarsman with his own boat anchored on the Ganga at the Bankipore Club, Patna. He would often row on the river, enjoying a pastime that complemented his disciplined lifestyle. Leila Seth once remarked that while K.D. Chatterji was an Englishman inside, Akbar was an Englishman both inside and out. Yet, this did not prevent him from adhering to the traditional practices of Indian lawyers, such as providing living accommodations for clerks and boarding facilities for clients from out of town. His home was impeccably maintained, with a properly laid dinner table every night, whether he had guests or not. He was also musically inclined, playing the grand piano every evening and often entertaining his dinner guests with Harry Belafonte songs.

His integrity and professionalism were evident in his conduct before the bench, even when the judge was his own father. On one occasion, with six cases listed before Justice Jafar Imam, Akbar requested that the cases be transferred to another court, citing concerns that his colleagues believed he would receive favourable treatment. Justice Imam declined, heard all six cases, and granted relief in four, denying it in two. The incident underscored the family’s commitment to fairness and justice, leaving no room for accusations of bias.

Tragically, Akbar’s life was cut short at the age of 43 while he was in London awaiting a kidney transplant. His premature death was a significant loss to the legal community, but his legacy lives on through his daughter, Tehmina Imam Punvani. Tehmina has upheld the family tradition, practicing law in Lucknow, Delhi, and Nainital. She was one of the earliest senior advocates designated by the Uttarakhand High Court, a recognition conferred by Justice S.H. Kapadia, the then Chief Justice of that High Court.

Akbar Imam’s life was a blend of brilliance, modesty, and a deep commitment to the legal profession. His story is not just a reflection of a bygone era but a testament to the values that continue to define the best of the legal profession in India. As we remember him on his birth centenary, his legacy serves as an inspiration for future generations of lawyers.